| The Petrie Islands: Naturally Special |

by Christine Hanrahan and Stephen Darbyshire

I. Introduction

Back in the 1970s the OFNC, concerned that nobody was looking out for the special ecological features of the Petrie Islands, called for stringent protection of the extensive marshes considered to be "among the finest in the Ottawa district below Ottawa itself" (Dugal 1977), and the flood plain forests (Reddoch 1980). At that time the islands were not faced with any immediate threat and so faded back into obscurity to be enjoyed by only a few fishermen, naturalists and local residents. It wasn't until a couple of years ago when the Township of Cumberland began showing an interest in the area as a potential location for a large marina complex to accommodate the needs of the east end's burgeoning population, that a concerned group of local citizens came together to form the Friends of Petrie Island. Added woes came with the news that the Region was eyeing this site for the proposed new bridge across the Ottawa River. Suddenly this once-hidden gem, tucked away along the Ottawa River shoreline east of Orleans became a hot item.

Not much more than 323 hectares in size according to Stokes (1996), this complex of wetlands, backwaters, flood plain forests, river shore habitat, riparian thickets, and open areas is a wonderful place for naturalists looking for somewhere new to explore. It is particularly enticing to those with an interest in plants. As one would expect, this diversity of habitat supports an interesting and varied assortment of flora and fauna. If you're looking for a challenge, there is much yet to record on the island for, to the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive surveys of plants and animals have been conducted and it is certain that many more species are waiting to be added.

Despite the sand extraction business which occupies the extreme north-eastern corner, the islands maintain an aura of timelessness, aloof from the cares and woes of the 20th century. Several footpaths wind their way across the area, giving rise to unexpected vistas. Turn this way and you're suddenly on a Louisiana bayou, turn another and you could be forgiven for thinking you'd time-travelled to an ancient rain forest. Meander past small sand dunes down to the river's edge and you're confronted with views that surely have changed little since the first white explorers paddled their way up the Ottawa. It is only later, with another bend in the shoreline, that signs of the modern world are revealed: Gloucester's distant highrises. It is easy to see why this place offers solace for awhile from our frantic and fast-paced lifestyles.

But how long will this peaceful little part of the world be spared? If the proposed developments ever occur, they would irreversibly change this site. Already the number of visitors has increased dramatically with the Friends of Petrie Island's new car park, summertime picnic facilities and frequent news coverage in local papers. Of course, one hopes that all these visitors will be seduced by the beauty of the site and lobby to preserve it from development. And yet... we cannot help but long for the days just past when these islands were little-known and infrequently visited.

II. Ecology of the Petrie Islands

These islands are a series of alluvial deposits forming a wetland complex of elongate sedimentary ridges and backwaters characteristic of the Ottawa River below the confluence with the Gatineau River. Along with Kettle Island and the Duck Islands, Petrie Islands form a unique landform in the region chronicling the powerful geological forces which shaped the face of our country. The sand and clay sediments that make up these islands were created by the massive icesheet that ground and polished the continent 10,000 years ago. Crushed by the continental glaciers from the rocks further north, the sediments were carried down the Ottawa and Gatineau Rivers. The river became a major route for plants and animals moving into Canada after the glaciation. Fine sediments would have provided the closest thing to soil available on the denuded landscape. From the patterns of plant distribution we can still see the effects of these processes today.

The unique habitats of the river corridor contain many plant species which reached their migrational limits along the floodplain forests and shores. Many species of plants can only be found in the region along the floodplain of the Ottawa River. Some of these plants require water systems and flooding for their seeds to be dispersed. Some need the continual shifting of shoreline sediments, while others need their habitat to be inundated in the spring but dried out in the fall. All of the plant communities found on the Petrie Islands are specially adapted to extensive spring flooding.

The power of the river and its seasonal fluctuations have shaped these islands and made them a special habitat for plants and animals. The islands are almost completely flooded in the spring, a special feature that many species are adapted to and may even require to maintain healthy populations. Continual erosion and deposition of sediments around the islands provides a renewal of shoreline habitats and an evolution of plant and animal communities. The quiet backwaters are extremely rich habitats providing shelter and abundant nutrients for a wide variety of plants and animals not found in the open river. The diverse mosaic of habitats, high-energy river shores, seasonally flooded forests, quiet backwaters, sand dunes, fertile clay soils, are all formed from the same processes, unique in the region to the Ottawa River. It is this variety of habitat that supports the many plants and animals of Petrie Islands.

At one time the types of habitats and communities found on Kettle Island, the Duck Islands and Petrie Islands would have been common along much of the Ottawa River shores between Ottawa and Montreal. Today, water level control from hydroelectric projects, development, shoreline armoring and farming have transformed the floodplain habitats. The natural environment of the shores, forests, and backwaters along the Ottawa River has all but disappeared and is long past regeneration, apart from a few areas such as the Petrie Islands.

III. Primary Habitats of the Petrie Islands

Wetlands, backwaters, and the open river

The extensive wetlands dominated by cat-tails (Typha latifolia) and bulrushes (Scirpus spp.) cover large areas providing excellent habitat for a variety of wildlife. Marsh wrens and the increasingly rare black terns nest in the marshes which also attract pied-billed grebe, American bittern and red-winged blackbird, and serve as an important stopover site for waterfowl during migration. The wetlands provide habitat for muskrat, beaver, and the occasional mink, and for amphibians such as bullfrogs, green frogs and leopard frogs. In the early 1990s the wetlands were designated provincially significant by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

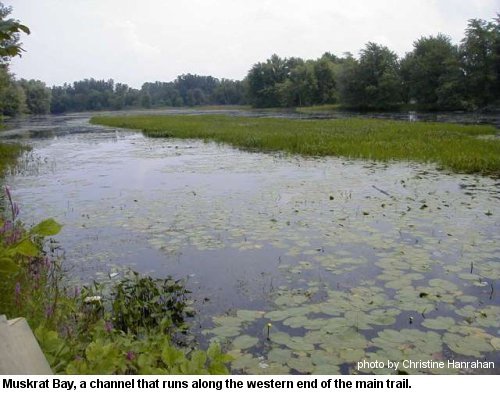

The quiet backwaters and bays with their growth of pickerel weed (Pontederia cordata), and water lilies (Nymphaea and Nuphar) and other wetland plants are the easiest places on the islands to see great blue herons, wood ducks, belted kingfisher and painted turtles. Shrubby thickets attract nesting common yellowthroats, yellow warblers and song sparrow, and a host of other species during migration.

The seasonal flooding of the Ottawa river creates special problems for the vegetation attempting to grow there. Plants that do survive are specifically adapted to withstand periodic inundation. A close examination of the exposed shoreline along Petrie Islands will reveal a number of interesting species of emergent flora such as Cyperus odoratus and C. diandrus, both considered regionally significant. Also able to survive annual flooding is the large stand of bladdernut shrubs (Staphylea trifolia) discovered in 1986 (Darbyshire 1987). These interesting plants produce fruit in the shape of bladders and when still hanging on the shrubs produce, in the slightest breeze, a soft, not unmusical rattling sound.

Spotted sandpipers frequent the shores, while ring-billed, herring, great-black-backed and occasionally other gulls can be observed from shore along with double-crested cormorants and in season, grebes, loons and diving ducks.

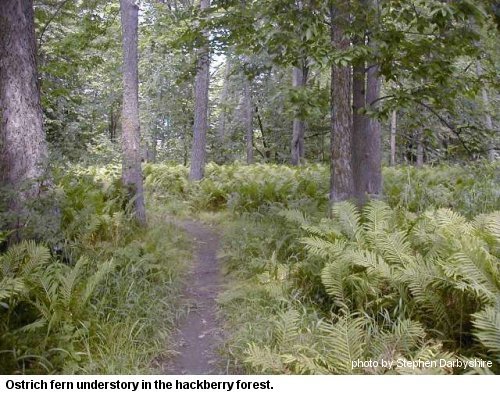

Flood Plain Forest

A significant portion of the islands are covered by flood plain forest. In 1977, Albert Dugal divided the woods into 6 zones and listed the dominant tree species on-site. Little has changed since then and mature specimens of butternut (Juglans cinerea), bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis), basswood (Tilia americana), American elm (Ulmus americana), red ash (Fraxinus pensylvanica), black ash (F. nigra), hybrid silver/red maples (Acer saccharinum × A. rubrum), and hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) still remain. The hackberry-butternut-bitternut hickory woods are a rather unusual forest association in the region according to Dugal (in Reddoch 1980). Of special interest is the extensive hackberry stand, considered by Dugal (1977) to be the "greatest known concentration... in the Ottawa district." The woods and adjacent shrubby thickets host a variety of birds in the different seasons including woodpeckers such as the large pileated woodpecker, flycatchers, great horned owl, black-capped chickadee, thrushes, vireos, warblers, rose-breasted grosbeak, and purple finch.

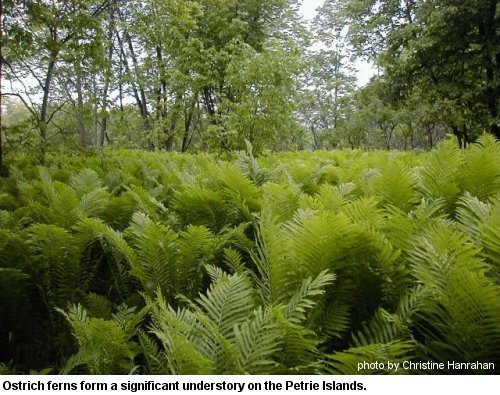

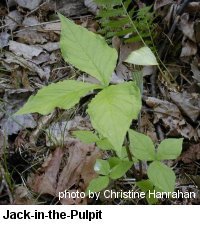

Dense, waist-high stands of ostrich fern (Matteuccia strutheopteris) are common in the woods, giving the illusion that one has sudenly wandered into a rainforest habitat. Keep an eye out for smaller fern species such as sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis). The uncommon vine carrion flower (Smilax herbacea) is a woodland dweller and can be found in the woods throughout the islands. When flowering in early summer it is usually first detected by smell as the greeny-yellow flowers are not visually conspicuous.

Open areas and trail-sides

The main walking trail (see below) on the principal island cuts through an open disturbed area for about the first half kilometre. A variety of plants may be found along this stretch including showy tick-trefoil (Desmodium canadense) and the regionally significant groundnut (Apios tuberosa). Bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) and tangles of wild grape (Vitis riparia) provide food for birds late in the season, while the abundant hog peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata) attracts the silver-spotted skipper butterfly. Disturbed areas are of course, colonized by a variety of non-native species and you'll see many familiar plants along the way such as thistles (Cirsium vulgare and C. arvense), Queen Anne's lace (Daucus carota), and white sweet clover (Melilotus alba). In the late summer of 1998 a new species for the area was detected, the non-native Galega officinalis, apparently known from only one other location in the region.

The main walking trail (see below) on the principal island cuts through an open disturbed area for about the first half kilometre. A variety of plants may be found along this stretch including showy tick-trefoil (Desmodium canadense) and the regionally significant groundnut (Apios tuberosa). Bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) and tangles of wild grape (Vitis riparia) provide food for birds late in the season, while the abundant hog peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata) attracts the silver-spotted skipper butterfly. Disturbed areas are of course, colonized by a variety of non-native species and you'll see many familiar plants along the way such as thistles (Cirsium vulgare and C. arvense), Queen Anne's lace (Daucus carota), and white sweet clover (Melilotus alba). In the late summer of 1998 a new species for the area was detected, the non-native Galega officinalis, apparently known from only one other location in the region.

Along the more shaded woodland edges grow a profusion of other species including a small stand of the uncommon white vervain (Verbena urticifolia), too close to the trailside and just waiting to be inadvertently cut.

The edges and open areas are used by a variety of sparrows, American goldfinch, gray catbird, cedar waxwing and brown thrasher. During a summer trip to the islands at the large open sandy area at trail's end, Christine watched young great crested flycatchers being fed, and found herself scolded and pursued by a family of vocal house wrens! An even greater diversity of birds can be found in these areas during migration.

IV. The Future of the Petrie Islands

Land-use Designation

The islands lie within the Township of Cumberland and were purchased in 1983 by the Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton except for several small parcels which remain in private ownership. The wetland complex surrounding the islands, has been designated by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) as a Provincially Significant Wetland as well as an Area of Scientific and Natural Interest (ANSI). The Regional Official Plan designates most of the islands and the shoreline as Provincially Significant Wetland, while the small areas of high land and the sand extraction operation are designated Waterfront Open Space. The north side of the North Service Road on the mainland is listed as General Urban Area in the Official Plan — Schedule B. The Regional Official Plan acknowledges the importance of protecting the islands' natural environment for wildlife, particularly waterfowl, and for the significant plant species onsite. The plan also recognizes the value of the islands for outdoor recreation. Under Cumberland's Official Plan, the islands are designated Open Space, with no recognition of their provincial and regional status as significant wetlands. Cumberland does note the inherent conservation values, but seems more concerned with their potential for recreation. Perhaps they are unaware that most forms of "outdoor recreation" are incompatible with conservation of natural values. It is unfortunate that the Township can't bring its designations into line with those of the province and the region. Why compromise the fragile natural characteristics of this unique site?

Development Plans

In 1998 the Township of Cumberland prepared a "Petrie Islands Master Plan." For anyone concerned about protecting the islands, this is a rather alarming document. Central to their vision is the proposed marina complex which could include, amongst many other features, an amphitheatre, club house, restaurant and large parking areas. For those seeking a simpler form of recreation, several large picnic areas and nature trails would be provided on the eastern portion of the islands, just to the west of the proposed marina. The land fill and asphalt required to fulfill these plans and the subsequent impact of heavy, mechanized traffic would irreversibly change the islands and degrade the special habitats.

Both the Region and Cumberland have their eyes on the Petrie Islands as a potential site for the much ballyhooed new bridge across the Ottawa River. While a bridge may at first glance seem to be less destructive of the natural environment than a marina complex, in reality bridge development brings its own set of disruptive forces which will compromise the unique ecological characteristics of the site.

It seems that the poor old Petrie Islands, once a forgotten backwater, have suddenly become a hot item in the minds of local officials; untouched and ready for development. That they represent one of the few remaining scraps of natural habitat left along the river between Ottawa and Montreal that is close to an original state doesn't seem to count in this game.

The best option would be to leave the islands as they are, with no further interference. But if some change is inevitable, why not opt for the least destructive? Passive recreation such as nature study, hiking, picnics and swimming, as defined by the Friends of Petrie Island (1998) is a good alternative to marinas and bridges. Unfortunately, increased usage by humans brings other problems and the greater the degree of usage the greater the potential for problems. However, it doesn't have to be this way. Sensitively designed picnic sites and trails will satisfy users and retain and protect the natural values of the area. Key wildlife habitats such as turtle and bird nesting sites and locations of significant plant species should be identified before any work is carried out. Naturalists need to be vigilant here, since ugly new trails have a habit of appearing overnight. If you think we're joking, take a look at the "trail" put in by the region last summer to get pedestrians off the road. The so-called trail is as wide as any road — or wider and appeared one day, a great ugly slash-and-hack through the woods. An embarassment to many, as it should be.

Too often trails are conceived of as narrow roads complete with paved surface. Why not allow trails to be "natural" footpaths that traverse a habitat with minimal intrusion? Cumberland Township is considering the whole question of trails along with interpretive signage for Petrie. The OFNC Conservation Committee has expressed their opinions on the subject and we'll see if they listened!

V. Flora and Fauna of the Petrie Islands

The flora and fauna of this site have not yet been properly inventoried and all lists are the result of casual observations or one-day site visits. It is apparent that further work would produce a substantial increase in the plant and animal species observed. Lists of species are provided in Appendices A to E.

VI. Exploring the Petrie Islands

A word of advice: these low-lying islands are flooded during spring and large parts are inaccessible to the walker.

The best and longest of the current trails is on the main island and leads west from the parking lot. It remains a dirt track past the two abandoned cottages and one still-occupied house, and then narrows to a grassy trail. It meanders slightly for some distance between a lazy slough on one side, replete with great blue herons, kingfishers, wood duck, mallards and painted turtles, and the Ottawa River on the other. Look for northern crescents, least skippers, viceroys and monarch butterflies along this stretch. Once past the end of the slough, the hackberry stand occurs just off the south (left) side of the trail, reached by a narrow footpath. The main trail continues past thickets of shrubs and trees with the occasional footpath cutting down to the river's edge. At one point, an almost indiscernible track leads north into the bladdernut shrubs, but you really need to go with someone who knows where they are to find them! Once past this spot, the land opens out into a scrubby sandy area fringed by stands of tall trees mostly eastern cottonwoods and the trail, for now at least, ends just beyond here. Another track leads down to a substantial beach (watch for poison ivy along the way) and some modest sand dunes.

For those wanting to explore further it is possible to follow a very faint trail carrying on past the open sandy area. Be warned, however, that it passes through damp to wet sections and soon enters dense groundcover that hides the many fallen logs. Waterproof boots and sure-footedness are a must for this area, but if you go slowly you'll be able to progress some distance until the trail fades completely. After that, it's up to you! This section of the island is somewhat different from the area you've just walked through. Now you're amongst tall trees, widely spaced, the ground covered with ostrich ferns high enough to occasionally obscure the view ahead. You might feel that you could walk for miles here. In fact, the island soon comes to an end and you find yourself once more on the shores of the Ottawa River.

Other footpaths probably made by fishermen, can be found leading away from the various pullover spots along the road. None of these are very long, but several offer different vantage points across the river and backwaters. One such path can be found on the north-east side of the causeway running along a finger of land jutting into the river. Here you may find common snipe in the fall along the edges, and out on the river various species of waterfowl depending on the season. Watch for bufflehead, red-necked grebe, lesser scaup and ring-necked duck in fall.

How to get there

Take the Queensway east and the highway 17 fork past Orleans to the Trim Rd. exit. Turn left onto Trim Rd. crossing the bridge to the islands and continue over a causeway and down the dirt road bearing left then right when it makes its sharp turns, to the north end where you'll find a parking lot provided by the Friends of Petrie Island.

For more information and updates on the Petrie Islands check the Friends of Petrie Island web site.

We'd like to thank Don Cuddy and David Miller for generously providing information on the Petrie Islands, Tony Beck for contributing bird observations and Peter Hall for butterfly observations.

References

- Brunton, Dan. 1998. Distributionally Significant Vascular Flora of the Region of Ottawa-Carleton. Prepared for the Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton, 36 p.

- Brunton, Dan and Bruce Di Labio. 1997. The Flora of Ottawa River Emergent Beaches. Trail & Landscape, 31: 109-123.

- Cumberland Planning Department. July 1998. Petrie Island Master Plan, Background and Issue Paper, 15 p.

- Darbyshire, Stephen. 1987. More on the Bladdernut Shrub. Trail & Landscape, 21: 26-28.

- Darbyshire, Stephen. 1997. A Red-eared Slider in the Ottawa River. Trail & Landscape, 31:157-160.

- Dugal, Albert. 1977. Petrie Islands Woods Resource Inventory. Prepared on behalf of the Ottawa Field-Naturalists' Club for submission to the RMOC, 11p.

- Friends of Petrie Islands. 1998. Petrie Island. Report to Cumberland Council, October 1998. Presented by Al and Helen Tweddle, 4p.

- Gillett, John M. and David J. White. 1978. Checklist of Vascular Plants of the Ottawa-Hull Region, Canada. National Museum of Natural Science, Ottawa. 155 p.

- Reddoch, Joyce. 1980. Response to the River Corridors Study. Petrie Island. Prepared on behalf of the OFNC. Stokes, Robert W. 1996. A comparison of the current wetland boundary mapping for Petrie Islands and Baie Lafontaine Provincially Significant Wetlands with mapping produced using the Ontario Wetlands Evaluation System, 3rd edition, 1993. 14 p.